I have worked as a journalist for over 35 years, as a reporter and editor for various newspapers and magazines. Before retiring in 2016, I was as an award-winning reporter and columnist for The Detroit News for 26 years.

I’ve been honored with numerous awards over the years, including the Best of Gannett Outstanding Achievement Award, the Society of Professional Journalism Awards, Associated Press Media Editors' Journalism Excellence Awards and the American Association of Sunday and Feature Editors writing awards.

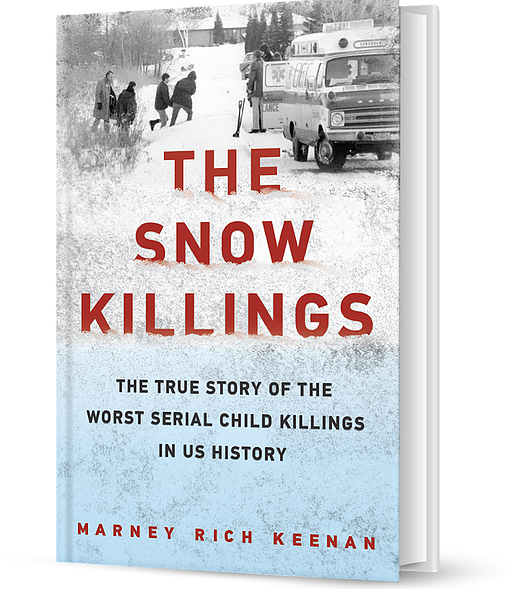

Beginning in February, 1976 to March, 1977 in Oakland County, Michigan, a child predator snatched four kids between the ages of ten and twelve from sidewalks and a drug store parking lot without anyone taking notice. There were no screams heard; no one reported seeing anything untoward. The children were held captive – it is not known where -- between four and nineteen days and then killed -- three were smothered one was shot – only hours before their bodies were placed by public roadsides where they were quickly spotted by passersby. Their clothes had been laundered; their bodies were so clean no residue of semen was found; particles of soap were found under one victim’s fingernails.

Ten million people lived in the metro Detroit tri-county area in 1976: media coverage saturated the state. No one had escaped knowledge of the largest serial murder in Michigan history, variously referred to as “The Michigan Snow Killings,” or the “Babysitter” (because the children had been fed and bathed). They lived through the dread of opening up the morning newspaper to find yet another elementary school class photo of a smiling child, the boldfaced banner screaming: MISSING. The cruelest part was the knowledge that each child was kept alive for the duration of their captivity; they’d been killed only within hours of their bodies being found. Until a body turned up, you knew the unthinkable was happening.

For the King family, life as they knew it - four kids in a three-bedroom ranch on idyllic, elm-canopied Yorkshire Road in the heart of Birmingham came to abrupt halt on March 16, 1977. Tim, then 11-years-old, was Barry and Marion’s youngest son. On that early evening, he’d borrowed 30 cents from his older sister Cathy and went up to the local drugstore with his skateboard to buy a candy bar. Meanwhile, Barry and Marion were having a nice dinner out at Peabody’s restaurant, kitty corner - literally a few hundred feet away - from the parking lot where someone coerced Tim into his car. Tim was missing for six days before his still warm body was found by the side of a road, his skateboard tossed as an afterthought.

Law Enforcement assembled the largest manhunt in the nation’s history at the time. Eighteen thousand tips had accumulated in those first few years, but in December, 1978, the task force formed to find the killer closed up shop without even naming a person of interest.

Police fielded tips as they came in but years turned into decades, memories faded and suspects died off. And then one July day in 2006, three decades after the bomb that was her brother’s murder obliterated any semblance of a normal future, Tim King’s older sister, Cathy King Broad got a phone call from that childhood friend of Tim’s who had lived across the street in that big white house. His information loosened a spectacular avalanche of evidence that had been locked up for decades in a records storage room in Michigan State Police facility.

It was all by design. The family of Christopher Busch had hoped we would never learn of their 26-year-old pedophile son. The police had a hand in burying the Busch evidence as well, lest the public know that Busch had been questioned a few weeks before Tim King’s murder and then released.

Chris Busch was convicted of raping minors four times over but never saw the inside of a jail. Busch’s father, H. Lee Busch, was Executive Financial Director in Europe and the United States for General Motors. He a paid a defense attorney large sums of money to fly across the state in the family personal plane to successfully plea bargain his son to probation in all four cases. The family lived in a sprawling five-bedroom home in Bloomfield Village, less than three miles from the Kings. Chris Busch died a year after the child killings stopped. The coroner said it was a suicide, but the evidence pointed to a murder. The Oakland County Child Killings Task Force shut down a month after Busch died.

Cathy King called the only detective she felt could trust. Not so coincidentally, Livonia Detective Cory Williams had a long-standing personal interest in the case. Williams’ father was also a detective, called onto to the case as a family friend when the third victim, ten-year-old Kristine Mihelich was snatched from the 7-Eleven less than a mile from the Williams’ home.

Once the thread was pulled, light was shed on the both the worst humanity has to offer -- the abhorrent evil that is pedophilia and its attendant corruption fueled by power and influence – and too, the best of us: a father’s four-decade mission for justice and a detective’s unrelenting quest to solve the case his father could not.